Militias on the eve of elections

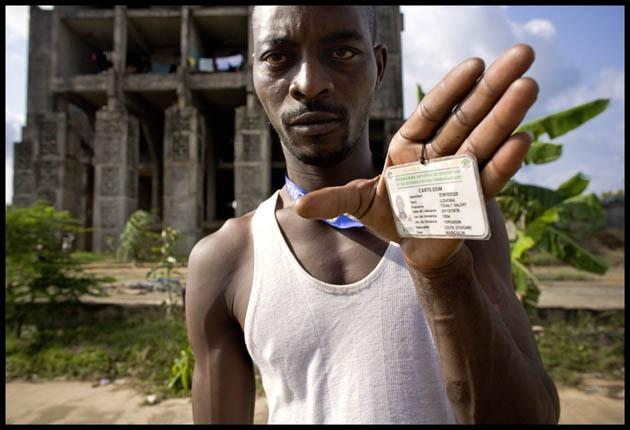

They call themselves “Groupes d'autodéfense” and describe themselves as patriots. They were founded eight years ago, shortly after the outbreak of the violent conflict that divided Ivory Coast in two. Many militia members ended up on the front line for a while, fighting alongside government troops against the rebels who occupied the northern part of the country. After a few months, the fighting was over and the long wait began: for real peace, for definitive disarmament and for elections. Many retreated to the economic capital Abidjan and set up camps. Since 2005, these have been systematically cleared by the army until only “Guantanamo” remained.

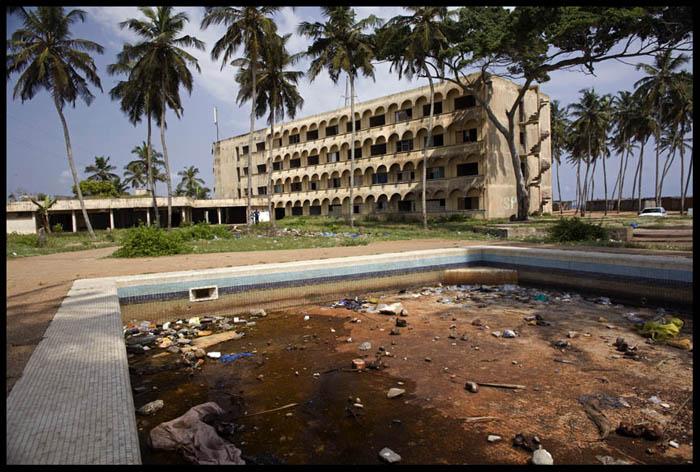

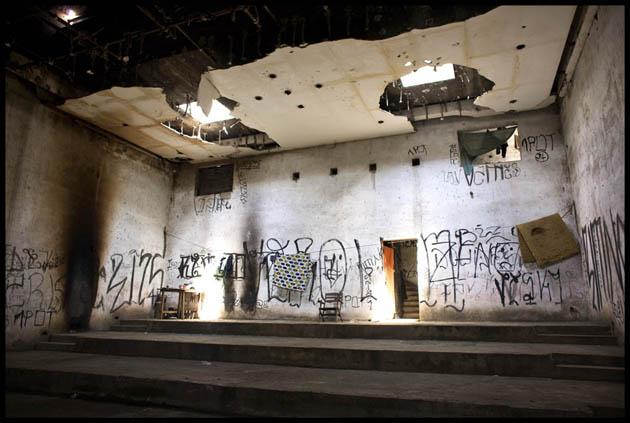

'Guantánamo', the place from which all this is being written, is five floors of weathered concrete in the middle of the city. Around a hundred former militiamen and their small families have sought shelter there. For them, “Guantánamo” is a safe haven: a base for their diverse but often futile activities in the urban chaos, but also a refuge from the brutal disregard of the elites whom they thought they had served with their patriotic violence.

Photo's: © Raymond Dakoua